Shabbat Gathering: Paper Towels

Dear Chevra, as is our custom, we will gather tonight at 5.45p ct to welcome Shabbat. These are the coordinates:

Zoom

Meeting ID: 963 5113 1550

Password: 1989

Phone: +1 312 626 6799

(To unsubscribe from the newsletter, click the link at the very bottom of this email.)

Writer's Note.

This is the 52nd Shabbat Gathering newsletter I've written for us. That adds up to about a year. And, we have 52 subscribers to the list. Thank you for all your support and encouragement.

Here we go.

It was two weeks before my wedding. (This was about 30 years ago in NYC.) My fiancé's beloved maternal grandmother Ida died. There was talk about postponing the wedding, but a rabbi was consulted and our plans remained in place.

When we returned from the cemetery to my future in-laws' home that very cold December day, there was a blue plastic basin of water and a roll of paper towels on their porch next to the front door. My fiancée, who understood I needed subtitles to move through her world, quietly explained that we were to wash our hands before entering her parent’s home. I was still new to NYC and Jewish culture and living in NYC for me wasn't just living in a foreign geography, it was tantamount to being on a very different planet.

People who attend a burial are considered tamei, ritually impure, and we needed to cleanse ourselves. At the time, I thought this was a bit much. If anything, I wanted to keep something of Grandma Ida with me. She had paved the way for me to join my new family and blessed our wedding. But rituals are rituals and I adhered to this one. I washed my hands in the icy water and entered the home where the mirrors were covered with sheets and the tables were groaning under the weight of the “appetizing” from a Brooklyn deli. The family sat close to the floor on what looked like cases of wine. Prayers were said. Stories were shared. Tears were shed.

I buried my mother and my aunt in last December. They were faithful Protestants. Their second homes were the church. There were graveside services. Prayers were said. Hymns were sung. Tears were shed. And that was it. There wasn’t tuna salad and bagels and herring in cream sauce. The mirrors were not covered. I did not sit close to the floor. But I had an online shiva for my mother and was greatly comforted by the people who attended. What rituals could I turn to?

Saying kaddish for a Presbyterian?

Following the week-long shiva period, the mourner’s kaddish is traditionally said every day for eleven months. A minyan is required to say the prayer. Today, we are blessed with online minyans and Beth Israel in Madison has one. The times I’ve attended, I saw familiar faces.

I don’t really know the protocol of saying kaddish for a Christian. I recently met with Rabbi Laurie but didn’t manage to get to that question. But saying kaddish couldn’t hurt. There are different reasons to say the prayer for the deceased. It’s suppose to help them merit life in the hereafter. But the prayer never mentions death or reminds us of those who have died. Some believe that the prayer is said for the benefit of the the survivors. I can use that support.

How to fill a grave.

Years ago, when I live in California, I belonged to a large Reform shul, Beth Emek, in the East Bay of San Francisco. Other than Chabad, we were the only synagogue in the area so we had a membership of Jews from many different backgrounds. An elder in the shul, someone much loved and respected, died and there was a large funeral in her honor.

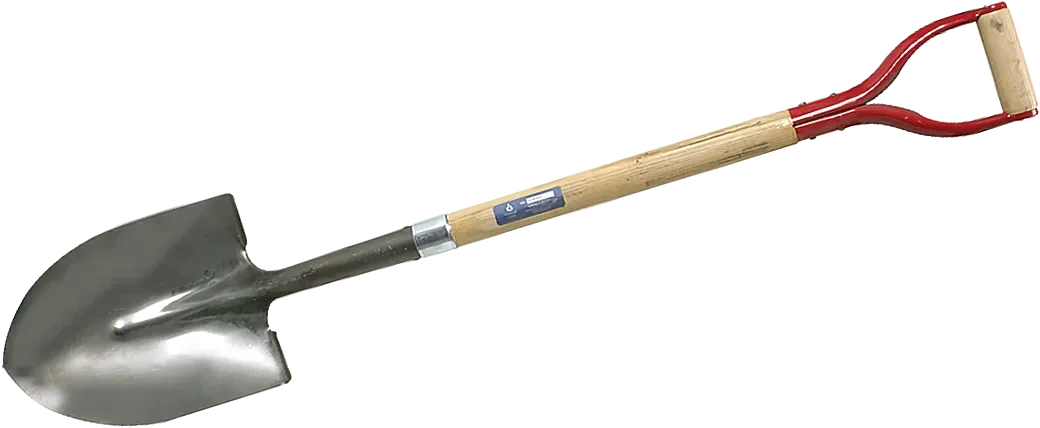

At the graveside, when it came time to shovel the dirt into the grave, I took my turn and was followed by a younger man who was originally from an ultra-orthodox community in New Jersey. He had gone off the derech (left the orthodox world), moved to California, married a Christian, and was starting a family. When he took the shovel from me, he flipped it upside down and used the back of the blade to put the dirt in the grave. Afterwards, as we were leaving the cemetery, I caught up with him and asked him about what he did and why. He replied that it was a tradition based on the notion it should be hard to shovel dirt into the grave. I was moved by this and decided this would become my tradition too. I was impressed with two ideas: how Jewish traditions are so deep and how our traditions are so right. It should be difficult to shovel dirt into a grave for someone we love.

In my own way, I’ll be saying kaddish for eleven months for my mother and aunt. Somedays, I’ll be saying it by myself with my iPhone, without the support of a minyan. Somedays I will say it with a minyan. And on Friday nights, I’ll say it with you. I don’t worry about my mother and my aunt meriting a life in the hereafter because they lived righteous lives. Mostly, I’ll be saying kaddish for myself in order for me to merit life in the hereafter.

Who will say kaddish for me?

I’m estranged from my daughters. Through my ex-wife, I know that they identify as Jews and I feel good about helping instill their identity. Knowing that I helped raise two more Jews in the world makes me feel good. However, I doubt they will say kaddish for me when I die. Rabbi Laurie told me that I can ask someone to say kaddish for me. She told me that this is a great mitzvah for someone to do for another. I casually mentioned this to someone I’m close to in Madison, and she told me that she would say kaddish for me. But I feel I need to be more explicit about the request, ask it more formally.

My intention is to move back to Madison. I’ve considered moving back to California or NYC, but I don’t feel, at my age, I can start my life over again even though I’ve lived there before. Besides, there are so many people in Madison I love. One of my motivations to leave Arkansas is to return from the galut (exile) to the mere diaspora. And, specifically, I want to be buried as a Jew, something impossible in Arkansas. I’ve been involved with Jewish death rituals for many years. In California, I worked for a while at a Jewish funeral home. In Madison, I represented our synagogue on the board of the Jewish Burial Association of Madison and have been asked to serve on the board again. And I will serve. I’ve served on the Cheva Kaddisha, the Jewish burial group that performs the death rituals. I’ve written articles about Jewish death rituals for the Forward and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. And I’ve experienced death in my family, just like every one else. Death is something I think about a lot.

I want a Jewish burial. I want to have tahara, the ritual preparation of my body for burial. I want someone to cut the tzitzi off my tallis to indicate I’m released from performing the mitzvot. I want shomers to guard my body and read Psalms until I’m buried. I want someone to use the back of a shovel when they cover my coffin with dirt. And I want someone to say kaddish for me. Unlike my mother and aunt, the way I’ve lived my life so far, I’m going to need some help meriting a life in the hereafter.

The struggle.

Jewish life means wrestling with the text, the halacha (laws), and the midrash (stories). And when living as a Jew includes life and death in galut, diaspora, and interfaith families, we struggle all the more. Jewish life has always outstripped our well-accepted ideas and traditions and will continue to do so. It’s up to us to write the new responsa necessary for us to get along in this wide world. So I struggle with what I'll do - as a Jew - about the death of my mother and aunt.

We rely on tradition and when tradition don't help us, we rely on our good sense. And when we apply our good sense, we rely on our imagination to create new rituals to make life and death more meaningful and memorable for us. This is the poetry of life we are writing.

I love all of you. I’m sorry if this newsletter has been a downer, but this is what’s on my mind as I struggle with starting a new chapter of my life. Every week on Friday nights, we speak about people we know who are ailing and we speak about those who have died. What I hope doesn’t escape us is that we also talk about creation and love and life. Sickness and death cast a dark shadow across our lives, but when we feel overwhelmed by the shadows we need to remember that shadows are created by the light.

And may it be for all of us a blessing.

See you tonight!

Gut Shabbes!

All my love,

brian.

PS

In my new life after Mom's death, I've been rediscovering the music I love. I can listen to what I want, whenever I want, as loud as I want. One of favorite artists is Rickie Lee Jones. Here's a song I especially like that describes the cycles of our lives. I hope you enjoy it.

-30-