Shabbat Gathering: Bilhah and Zilpah: Matriarchs?

Dear Chevra, as is our custom, we will gather tonight at 5.45p ct to welcome Shabbat. These are the coordinates:

Zoom

Meeting ID: 963 5113 1550

Password: 1989

Phone: +1 312 626 6799

(To unsubscribe from the newsletter, click the link at the very bottom of this email.)

Here we go.

In the Avot v’Imahot we say, “…G-d of Abraham, G-d of Isaac, and G-d of Jacob, G-d of Sarah, G-d of Rebecca, G-d of Rachel, and G-d of Leah…” This hasn’t always been the case. In my own lifetime, the matriarchs were added to this prayer, showing us our liturgy can, and should, change for the better. Some congregations are considering adding Bilhah and Zilpah to the prayer. They too are mothers of our twelve tribes. Here’s a look at the story of Bilhah and Zilpah and how they fit into the matriarchy.

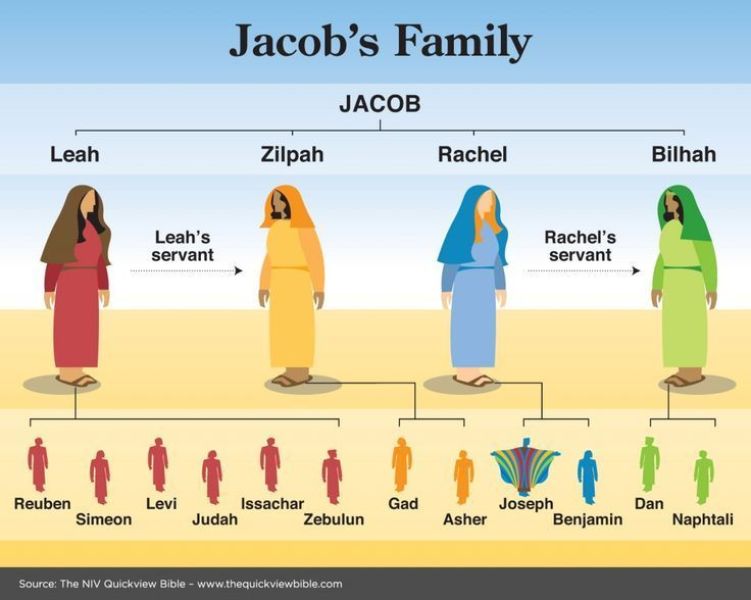

For those of you who need a reminder of the story, when Jacob finally married both of Laban’s daughters, Leah and Rachel, and set off on his journey, Laban gave his daughters handmaidens as a going-away gift, Bilhah to Rachel and Zilpah to Leah. Later, when a fertility competition breaks out between Rachel and Leah, Bilhah and Zilpah are drafted to bear Jacob more sons. Bilhah is the mother of Dan and Naphtali. Zilpah is the mother to Gad and Asher. Furthermore, the rabbis in Talmud suggest that Bilhah and Zilpah helped raise all the brothers. But the traditional reading makes it clear that Bilah and Zilpah were only surrogate mothers to their sons.

Who did Bilhah and Zilpah worship?

From the text, it’s unclear whether Bilhah and Zilpah worshiped the G-d of Abraham or the gods of Laban, or worshiped anything at all. To say in our prayer, “…the G-d of Bilhah and the G-d of Zilpah…” might be wishful thinking at best and possible sacrilege at worse. That would be bad.

I want to be sure that what I’m praying is accurate and true. I checked with Chabad because they have an easy-to-find, documented position on everything. Their conclusion is Bilhah and Zilpah were indeed holy, but not as holy as Rachel and Leah. Bilhah and Zilpah are considered lower-status individuals.

“Lower status” is a trigger for me. I’ve been involved in far, far left politics for a very long time. Issues relating to social status have been on my mind since before I was even a teenager. Because of that, after reading what Chabad had to say, I found the arguments for including Bilhah and Zilpah beginning to resonate more for me.

There’s a lot about status in Torah. In Parsha Korach for example, there is a rebellion against the religious hierarchy and the rebellion is famously put down when Hashem opens the earth beneath Korach and the rebels and they fall directly into sheol. On the other hand, there’s the lesson we learn from Parsha Beha’alotcha. Moses appointed new prophets and created a new level of hierarchy. When it was reported to him that others outside that hierarchy had become prophets too, Moses replied, “Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets, that the Lord put His spirit upon them!” As usual, the lessons are ambiguous.

Then, there’s the character of our synagogue. We describe ourselves as an “inclusive Jewish community” and we live up to that. We are the Reconstructionist and Renewal shul in Madison and trend towards the far left edge of Jewish life here. We experiment with new forms of liturgy and practice, and therefore incorporating Bilhah and Zilpah seems to be fitting for us. As our synagogue is about inclusion, so we should include Bilhah and Zilpah as part of our matriarchy.

Bilhah and Zilpah and me.

All this talk about whether to include Bilhah and Zilpah make me think of my own inclusion in Jewish life. I converted in a Reform synagogue and thus, according to the laws of Israel, I am not a Jew. That’s ok with me because I have no desire to make aliyah. (That’s a whole other story). But as if being a self-conscious Jew isn’t hard enough, I also have to deal with people who don’t think I’m a Jew, and this just reinforces my self-consciousness. I’m someone who believes he stood at Sinai yet still has to contend with being “other.”

Throughout history, Jews have been the “the other,” outsiders to the world just as Bilhah and Zilpah are “others” in our own midst. Not recognizing Bilhah and Zilpah as matriarchs means we haven’t learned from our own story. Including Bilah and Zilpah means we understand that there are people in our midst who are essential to our narrative and this is the real story, not an edited version. Not embracing these two matriarchs means we take the same cudgel that’s been used against us for centuries and use it on the family in our own tent. And that’s a shonda.

Including Bilhah and Zilpah.

I’m for including Bilhah and Zilpah exactly because of the ambiguity of the issue. There are many Jews in this world who have ambiguous roots. When I am called to Torah for an aliyah, the rabbi says I’m the son of Abraham and Sarah, and that’s a signal to the minyan that I’m probably a Jew whose ancestors are beyond the twelve tribes. It’s also a signal that I’ve accepted the mitzvot and should be included. I’m included. I’m included not just in the celebration of the motzi and the kiddush, but in the obligation of the mitzvot. The synagogue is home, and this means that I enjoy the challah and grape juice and do the dishes afterward.

Including Bilhah and Zilpah in the Avot affirms that all Jews have reached the present moment from roots that might include the ger toshav and the nokhri, the fellow traveler and the stranger. Accepting Bilhah and Zilpah says that regardless of where we’ve come from, we have arrived. We now stand as one before the Torah and our G-d.

And may it be for all of us a blessing.

See you tonight!

Gut Shabbes!

All my love,

brian.

PS

I recently read and enjoyed, My Name is Asher Lev (1972), by Chaim Potok. The book is about the internal and external conflicts of a young man who is a gifted artist and his upbringing in a Chassidic sect that doesn’t value art and, in fact, denigrates it as a indication someone has come under the influence of dark forces. I learned a lot about Chassidic theology from reading it. I also learned how a talented writer, Potok, describes the way a talented artist visually understands the world around him.

PPS

Today's my birthday!